Keeping it Real

An experience of the little-known illness that is Depersonalization-derealization disorder.

Something that was not there before

has come through the mirror

into my room.

It is not such a simple creature

as at first I thought —

from somewhere it has brought a mischief

that troubles both silence and objects

and now left alone here

I weave intricate reasons for its arrival.

They disintegrate. Today in January, with

the light frozen on my window, I hear outside

a million panicking birds, and know even out there

comfort is done with; it has shattered

even the stars, this creature

at last come home to me. - The Beast - Brian Patten

One evening, after the rite of passage that was drinking too many Pernod and blackcurrants in the pub that wasn’t too fussy about our age, maybe I was 16, myself and two friends carried each other home. I remember my aunt met us at the door for some reason. There was no drama, my Auntie Wendy wisely ushered her staggering nephew towards the sofa where I slurred volubly to my parents about whatever nonsense was simmering under the surface of my teenage brain, to much laughter.

I remember noticing, out in the driveway, as if out of the corner of my eye, that the world, in a way independent of my being drunk, had somehow altered, very slightly. For a moment I could observe myself, as if from without, as though I were a puppet master, enacting each moment of being from a little distance. I soon forgot this incident of perceptual strangeness, or at least, because I’m recalling it now, filed it somewhere for later reference.

That summer we moved from Solihull, where I’d spent all my life, to a village outside Exeter in Devon. I suppose it was a big upheaval, leaving all my friends behind, but I was excited. In Solihull I’d been a dorky swat, good at school, hopeless at sports, not very lucky with the girls. My drama teacher in her final report had remarked that she hoped I would leave behind my cynicism as an ‘unnecessary defence’. Moving to Devon gave me the perfect opportunity to reinvent myself and indeed I did. I bought an Afghan coat, joined the Worker’s Revolutionary Party, drifted into the company of the stoners and ‘got-off’ with pretty girls at parties. I remember my dad, smoking as he looked out over the back garden, a good man, trying to deduce how to manage this troubling set of evolutions. My uncle Tony remarked that it was me ‘just trying to find my way in the world.’

I read Huxley, Kerouac, Ginsberg, felt the need to push at the ‘doors of perception’. I listened to Gong, Hawkwind, early ‘Floyd, all the stoner standards of space-rock and retro-psychedelia. If this piece had a soundtrack, it would be Gong’s ‘Fohat Digs Holes in Space’, still a classic of the genre. I’m listening to it now.

One of my stoner friends, who later crashed his motorbike aged 17 and was paralyzed from the waist down, lived at the time in a manor house with his Major-General father and rather doughty mother, where they bred hunting dogs. Our psychonautic adventures took place in his suite of bohemian attic rooms at the top of the house, or exploring the fields and barns around the farm. His parents seemed oblivious or indifferent to their son’s intensely variable countenance, to the endless comings and goings of his addled and eccentric circle of friends.

A few weeks after one such sortie, one I won’t describe in detail here, because it has informed a spiritual worldview and merits its own piece, I woke up to get ready for sixth-form college as I would any other weekday in January. Something wasn’t quite right. I couldn’t quite put my finger on it, but it was almost as if the world had shifted tangentially by a few degrees. The feeling soon subsided.

The following day it was back, a little more intense perhaps, longer lasting, worrying me now, and deeply unpleasant. I’m a poet, (quite possibly because of this experience), so you’ll have to tolerate strings of metaphors in an attempt to describe what began to unfold, as day by day it accelerated, became entrenched, and came to dominate my every waking hour.

At first it was the world that left me. As though a grey veil of unnerving unfamiliarity were drawn over every perception, every well-known place and person oddly stripped of intrinsic connection and meaning. This intensified, to the point where it began to inspire a smouldering panic. A horrible part of this process was that, at least at the start, I would sometimes wake into a bright lucidity, the same as always, only to feel it slide inexorably away as the veil descended. This also sometimes happened after periods of intense concentration; I would look up from reading to see the world in all its crisp and familiar definition, but be unable to stop its determined retreat into the fearsome fog.

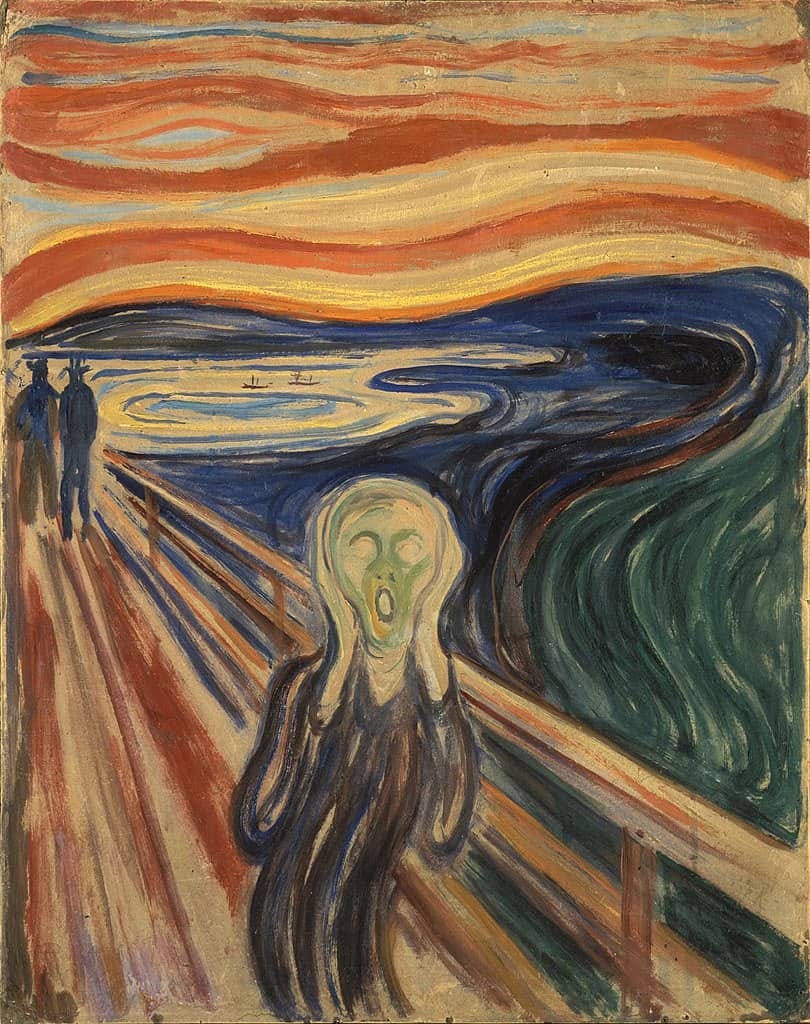

Over time, these tantalizing interludes of lucidity left me altogether, and this curious, frightening and nameless phenomenon took a new, dark turn. I began to lose any sense of myself. Where the faces of others; family, loved ones, had become uncanny, unmoored and alien, now it was my turn. I would look into the mirror, riven with silent and solitary terror while I brushed my teeth, to see the face of a stranger looking back at me. This too, intensified.

After a few weeks of this, I plucked up some courage and went to see the family doctor, an experience of incompetence so dispiriting I wished I hadn’t bothered. Rather bravely for a 17-year-old, I explained to the haughty lady doctor how I’d dabbled with acid and now felt really weird, asked was there anything to be done, was there any medication that could stop this horror in its tracks. She explained that then I’d just become ‘hooked on medical drugs’ for some reason, though there was no question of any kind of addiction whatsoever. Worse than useless, she somehow later contrived that my mother would catch sight of the notes she’d taken that day.

Untethered from myself and my world, and still in essence a child, I was helpless, as meaning, connection and every pillar of a rooted identity slipped away into a dark and blunted hinterland. My personality, my every action, felt like a dull, performative masking. Every word I spoke was uttered by a hollow and alien voice, as if overheard from another room. It began to affect my vision, as a literal fog. Panic attacks, whether as a symptom of the illness or simply a response to the dread it inspired, became commonplace.

In the interests of brevity, I won’t detail every episode I later suffered, six in all, lasting from my late teens until my early 30s. Some were worse than others, of longer duration or greater intensity. Some of the episodes had a clear trigger; spiked at a party in Spain the day before returning to England, or unwisely experimenting with magic mushrooms, for example. One time, the last, it set itself in motion after a heavy night out with friends in Brixton drinking caipirinhas. On a couple of occasions the dread retreat from reality had no discernible trigger. I once woke up in the back of the car returning from a visit to my grandparents and I was already a long way down the terrible road.

In my case, mercifully, these episodes were self-limiting. They would reach a peak, where I floundered in a mess of existential loneliness and despair, then plateau, before slowly the tide would begin to go out after a few months and I would rebuild a sense of self, a sense of my rootedness in the world, as it resumed a new, albeit looser definition. At the time, I always felt as though my entire personality had been stripped away, and like some kind of time-lord, I’d start from scratch with a new, self-build simulacrum of a me. There seemed to be no continuum of selfhood connecting me to the boy I’d once been.

Of course I didn’t know this the first time. Frightened and alone, my academic progress took an unsurprising nose-dive I only just managed to recover. In fact, the act of focussing on my A-levels was a part of my process of recovery. Nevertheless, the promise I might have shown was not fulfilled, as repeated episodes of illness followed me to university, perhaps provoked by the change of environment.

After the Spanish spiking event, thrown onto the mercy of some friends and living in a tiny shack in the New Forest, I was sufficiently despairing to take a rope out into the woods in the dead of night, considering the obvious. I bottled out, thankfully, and later pushed myself to visit friends in Ireland while I was still in the thick of it. When I returned, a huge, flowering cherry tree that stood over the shack was in full blossom and I knew I was turning the corner. I visited a spiritual healer, who did, well, something that must have worked. Nevertheless, I’d already made another visit to the doctor, was referred to a psychiatrist, and for many years carried a letter with me suggesting, should I present in this condition, that I be bombarded with anti-psychotic medication. Thankfully, I never had to resort to this questionable solution.

It was only a couple of years ago, entirely by accident, that I discovered this to be now a well-defined and reasonably well-understood mental illness, known as Depersonalization-derealization disorder, DDD for short, with an incidence in the general population of around 1-2%. It is not uncommon for many people to feel a transient dissociation similar in nature, but in its form as a full-on mental illness, the effects can drain lives of colour for months, as in my case, or even years. The triggers are hypotheses at best; drugs, obviously, a predisposition of some kind, or a dissociative response to emotional trauma, of which I had none.

I have failed here, to bring to bear any metaphors that might do this existential horror justice. It is like trying to explain to someone the loss of something they didn’t know they had, so intrinsic to one’s sense of self are the mechanisms that invisibly bring this construct into daily being. I was very lucky, as a survivor, to have been equipped with some kernel of internal resilience that saw me through the dread months of the evil Tír-na-Nóg.

Writing this, and thinking about writing itself, I realise now, after 27 years free of this terrible, miserable illness, I can extend my hand to the promising, tousle-headed boy I once was, and know we are, at long last, one and the same person. He would be pleased to see some level of potential fulfilled, in my trifling little wins as a poet and a writer. In the out-breath that has been writing this, both he and I have been moved to tears of relief and gratitude.

If you would like to know more, or if you or a loved one have been affected by this, I suggest engaging with the UK charity Unreal:

This was a great read. I'm glad you don't have what seems a bit like "splitting" or dissociation any longer. I think that's usually a result of trauma although you state you never had trauma.

Some people just are very sensitive and the pressures on you in adolescence tend to find these cracks and widen them.

These people often go on to be very creative. You are, so I'm wondering if you sense any truth in the sensitive nature idea?

Was it writing which enabled you to get through the worst of it and come out the other side?

After reading this, I have nothing but admiration for you James, and I mean on many levels. I'm very glad you walked out of that forest and are still here today. I'm also glad the last 27 years have been DDD-free for you. If you're ever in Barcelona, pleas make sure you let me know.